REALITY: The way things really are

Finding the inner animal

1. Monkeying Around

In this remarkable painting, a monkey is performing the Sanbaso, a dance celebrating the New Year. Dressed in a kimono and a black cap, the monkey holds a fan in his left hand and a cluster of bells in his right hand.

But wait! Monkeys don’t wear kimonos and dance. Or do they? This may be a portrait of a tame monkey dressed as human. Although few monkeys would voluntarily dress up, they often seem to have human qualities even without wearing clothes. They scamper and play, just as humans do. They are curious, and sometimes they are very mischievous.

We can see many of the monkey’s inner qualities in this work. The artist, Mori Sosen (1747-1821), studied monkeys just as closely as earlier artists studied the works of traditional Chinese artists — as he probably did himself in his training as a young artist.

Mori Sosen created this painting to celebrate the Year of the Monkey in 1800. One of twelve signs in the Chinese and Japanese zodiac, the Year of the Monkey is said to be a time of success in business and diplomacy. People born in the Year of the Monkey are believed to be clever, vain, and high-spirited.

The Japanese macaque or snow monkey has a special position in the hearts of the Japanese. The macaques, who inhabit Japan’s mountainous countryside, are mischievous pests who steal food. But they also have a good side — they are considered messengers of the Shinto gods of various mountains. The Japanese macaque has been a favorite subject of artists for its human look and behavior.

Mori Sosen used a dry brush to create the realistic and ruffled texture of the monkey’s fur, in contrast to the smooth, unpainted surface of the kimono. With fine, deliberate lines in dark ink, he masterfully captured the fixed stare and the mouth pursed tight with concentration of the dancing monkey. Sosen, Japan’s foremost painter of monkeys, was able to capture their character so well that his contemporaries accused him of being descended from monkeys.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, many artists, most famously Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795) and Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), depicted living animals and birds in their work and encouraged other artists to use them as models. This approach led to more realistic depictions, with increased attention to physical volume and to feathers, hair, and other surface detail.

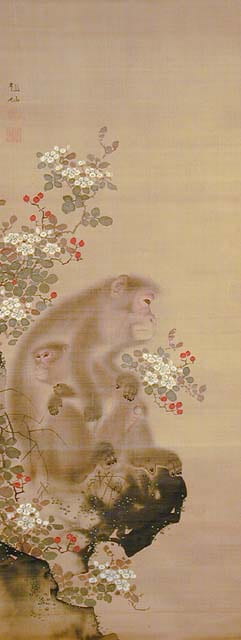

In observing animals and plants, these artists often caught the essence of a moment in time, such as this tender scene between a snow monkey mother and her child.

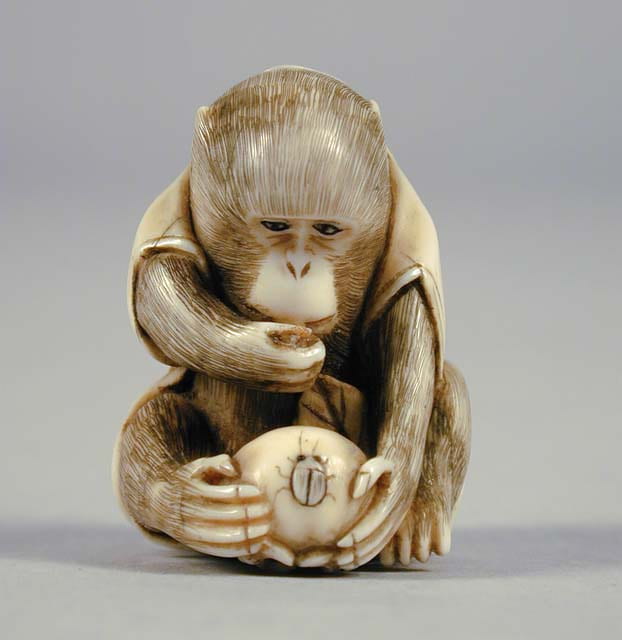

This tiny sculpture, carved in ivory, can be held in the palm of the hand. Even so, the carver has conveyed a monkey studying a beetle with the greatest realism, capturing the monkey’s curiosity and wit. Even the persimmon and the beetle that make up a part of this netsuke are rendered so that they almost appear real.

Many Japanese artists of the Edo period seemed to be able to get inside the minds and bodies of the animals they depicted. A deep understanding of nature connected artists with even the smallest and least significant of creatures: a snail, a beetle, a sparrow.

Monkey Performing the Sanbaso Dance

Mori Sosen (1747–1821)

Dated 1800, the first day of the Monkey year

Scroll painting, ink on paper

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Bruce Ross, 1985.55.4

Monkey with Baby and Autumn Flowers

Attributed to the school of Sosen

After 1800

Scroll painting, ink and colors on paper

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Dr. George W. Housner, 2001.21.81

Monkey Netsuke

Late 19th century

Ivory

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Elinor D. Herrick, 1997.15.39

2. The Tiger Within

In this drawing, artist Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) shows that a painting does not have to be realistic to capture the inner animal. Hokusai’s beast is full of power and vitality even though it does not look much like a living tiger. It is clear from the size of the creature’s head that Hokusai had never seen one of the huge felines, yet the beast is very lifelike. It peers around inquisitively and looks as if it is pacing restlessly. Like real tigers, Hokusai’s animal is striped but with red brush strokes in a reversal of a tiger’s actual coloring.

In China, the tiger was traditionally one of the animals that guarded the four directions of the universe. The tiger guarded the west, and is traditionally paired with the dragon, which guarded the east. The two beasts represent the two opposing forces in the universe, yin (tiger) and yang (dragon), and are often depicted together in Chinese and Japanese paintings. Here, the tiger is the companion of one of the Immortals. The drawing is a one of a series of preparatory drawings for a hand scroll depicting Chinese immortals of the Taoist tradition.

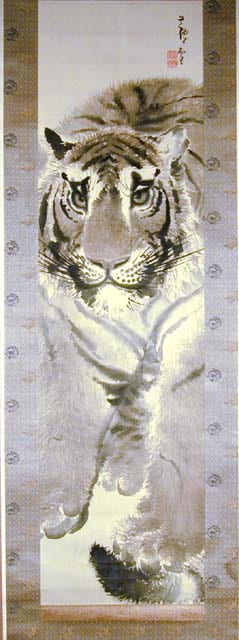

In contrast, Nagasawa Rosetsu (1754-1799) painted a highly realistic image of a tiger. The great beast stares straight ahead as if challenging the viewer to come any closer. The narrow composition of the painting, in which the tiger appears to be bursting out of the frame, adds to the sense that the tiger is menacing the viewer. The essence of the tiger, a powerful and fearless beast, is captured expertly in this ink painting.

It is believed that the artist, Rosetsu, had never seen an actual tiger, let alone approached a tiger so closely. However, he was very successful at depicting a lifelike representation. For the fur, he painted hundreds of tiny lines in several shades of paler ink, on top of which he added black lines with a wet brush while the pale ink was still damp, creating a smudged effect. In contrast, he painted the tiger’s powerful face with a relatively dry brush and black ink, and painted the piercing eyes staring at the viewer to enhance its lifelike quality.

Study of a Tiger

Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

circa 1835

Ink on paper; originally a section of a scroll

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Herman Blackman and Barbara Lockhart Blackman, 1985.58.7

Tiger seen from the Front

Nagasawa Rosetsu (1754-1799)

circa 1780s

Scroll painting, ink and color on silk

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Gerald Kamansky, 1985.56.4

3. Eagle-Eye Views

An eagle stands defiantly on a rock in the face of a violent snowstorm, facing the storm without seeking shelter. The eagle is a symbol of strength and power in Japan, and paintings of eagles and hawks were highly prized by Japan’s military leaders.

Undoubtedly drawn by the artist Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) from a living Golden Eagle, the bird is painted with great depth and anatomical accuracy, its chest feathers painted with a dry brush to appear ruffled in the strong wind, and its wing feathers painted in layers with shading to create a sense of volume. The eagle’s talons are also drawn very carefully, shown tightly gripping the rock, and its eyes stare piercingly into the blustery sky. The only aspect of the painting that is not realistic is the stylized rocky landscape in the background, which contrasts with the vitality of the great bird.

Hokusai, who had painted since the age of five, worked tirelessly throughout his long career to depict the true essence of animals. In his mid seventies, Hokusai described his own artistic progress: “At the age of 72, I finally apprehended something of the true quality of birds, animals, insects, fish and of the vital nature of grasses and trees.” He added that if he lived to the age of 110, each dot and line of his paintings would possess a life of their own. Eagle in a Snowstorm was painted the year before his death at the age of 88 and possesses a great vitality. It is signed Gakyorojin Manji yowai hachi-ju-hachi sai, “old man crazy about painting.”

Hokusai’s contemporary, Ando Hiroshige (1797-1858), presents a spectacular view of the wetlands of Fukugawa from an eagle’s perspective. He includes the eagle in the scene, which adds a sense of omnipotence and detachment. The Fukugawa area, located on the outskirts of Tokyo, flooded in the late 1700’s, which the artist may have been envisioning near the end of his life.

Eagle in a Snowstorm

Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

1848

Scroll painting, ink and color on paper

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. George A. Brumder, 1986.113.4

Ten Thousand-Acre Plain at Suzaki Fukagawa, from the series “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo”

Ando Hiroshige (1797–1858)

19th century

Full-color woodblock print on paper

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Dr. George W. Housner, 2001.21.17

4. Animal Happiness

Japanese artists often painted or made prints of fish. An important staple in the traditional Japanese diet, fish are also graceful and sleek and can symbolize endurance and long life. In this painting by Ando Hiroshige, two trout are shown swimming in a stream. They are rendered in a “boneless” technique, in which volume and shape are suggested by graded washes of color instead of painted outlines. This technique is skillfully used here to create a sense of the fish gliding smoothly through the water.

Hiroshige is best known for his series of prints entitled The Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido Road, but he was also an accomplished painter who studied many artistic styles. A great master of landscapes and bird-and-flower paintings, he produced many realistic depictions of birds, insects, and fish. He also created several illustrated books and print series dedicated to Japan’s many fish species.

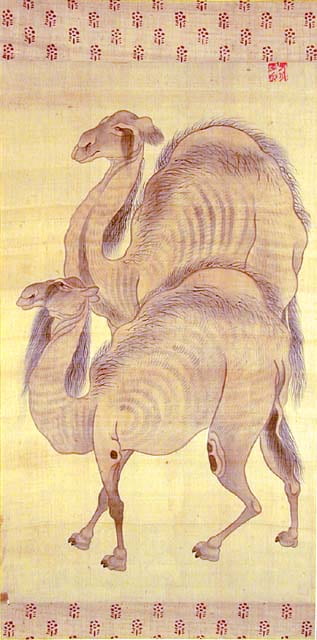

In 1824, two camels were brought to Japan from central Asia and were toured around the major cities. The camels, a male and a female, were rare in Japan, and artists flocked to observe and paint the unusual creatures. Several representations of the camel couple exist by different artists.

Tani Buncho (1763-1840), an artist who is better known for Chinese-style landscape paintings, has made a genuine attempt here at a realistic depiction of these creatures. Their coats have been carefully painted, hair by hair, and their rather smug facial expressions have been faithfully reproduced. He has painted concentric lines in a pale ink and then covered them with tiny hair-like brush strokes to add dimension to their bellies.

Two Trout in a Stream

Ando Hiroshige (1797–1858)

circa 1830

Scroll painting, ink and color on silk

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Herman Blackman and Barbara Lockhart Blackman, 1986.94.10

Two Camels

Tani Buncho (1763–1840)

circa 1824

Scroll painting, ink and color on silk

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Eleanor T. Nordskog, 1996.22.1

5. The Spirit of Nature

Hayao Miyazaki’s 1997 animated film (or anime), Princess Mononoke (Mononoke-Hime), may not seem like a realistic exploration of environmental issues in contemporary Japan. Yet this movie, Japan’s top-grossing film the year it was released, taps the spirit of the natural world in the same way that artist Mori Sosen explored the true nature of monkeys.

This complex and dark anime is set at a time when most humans live happily and in harmony with nature. Yet the world is changing — some people have begun to exploit and make a profit from the natural world. As a result, a disease contaminates the ancient forest, whose animals and spirits are also threatened by pollution from iron mines.

San, a girl raised by wolves, and Prince Ashitaka seek to save the forest. The forest itself comes to life and takes the form of a mysterious Forest Spirit. This awe-inspiring creature is as huge as Godzilla. However, it is also beautiful in a strange and eerie way — it has the body of a stag and a face that is almost — but not quite — human.

Many of the animals in Princess Mononoke are bigger than life or are monstrous blendings of living animals. Even though they are supernatural, however, they still contain the essence and spark of life, and are as convincing as any animal in the real world.

New York Times critic Janet Maslin noted, “Absent are the little anthropomorphic touches that enliven most animation involving animals; this film’s prevailing attitude toward its creatures is one of respect and wonder.” In its depiction of the nature of animals, Princess Mononoke inherits the legacy of the great works of Japanese art.

Princess Mononoke

Hayao Miyazaki

1997 / Film

Studio Ghibli