TRADITION: The way we have always done things

Artworks of animals mirror human and the heavens.

1. A Powerful Bird

If you are a sparrow or a mouse, what could be more frightening than the shadow of a hawk or a falcon hunting overhead? Even a hawk sitting on a branch attracts crows and jays, which try to scare it away from their families and their nests. Hawks, falcons, and eagles are powerful birds.

Many Japanese artists of the Edo period created their works for powerful men — the wealthy and mighty nobility and warriors who ruled Japan. These men saw themselves in the hawk’s ruthless strength. Some warriors trained falcons as hunting birds or kept them as symbols of military might. They avidly collected Chinese paintings of hawks to decorate their homes.

For centuries, the artists of Japan took their methods and subjects from the Chinese. Japanese artists of the Edo period in Japan (1603-1868)used Chinese paintings as models for their works, observing closely how the Chinese master painters depicted their subjects. This painting of a hawk is attributed to Hasegawa Tohaku (1539-1610), an artist who worked in traditional Chinese ink painting styles. Tohaku trained under Kano school masters, who created Chinese-style landscapes and animals in a very stylized, decorative manner.

In this painting of a hawk or goshawk, the raptor has been painted very formally with detailed attention paid to the feathers. However, its stiffness suggests that the artist did not copy from a live hawk, but instead from another painting. The painting was one of a series of six that formed the panels of a folding screen that probably decorated the home of a samurai.

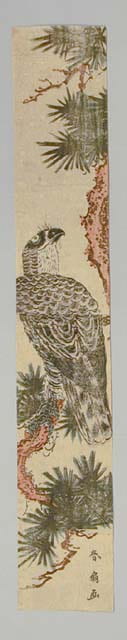

The artist Shunsen created a woodblock print of a hawk perhaps two hundred years after Tohaku’s work — and yet in many ways it is very similar. In this study Shunsen continues the Japanese tradition of depicting birds of prey — again, probably working from an earlier painting or print rather than observing a living bird.

Because numerous prints could be produced from wood blocks — notice where the two wood blocks used to print this work join in the middle of the hawk’s body — the potential audience for this work probably included merchants and tradesmen and not just Japan’s military class. By the nineteenth century, Japan’s merchant class had gained some clout from the samurai and possibly saw themselves as a power to be reckoned with in Japanese society.

Falcon [Hawk]

Attributed to Hasegawa Tohaku (1539–1610)17th century

Ink and color on paper; originally one panel of a six-panel screen

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Herman Blackman and Barbara Lockhart Blackman, 1986.94.12

Eagle [Hawk] on Pine Branch

Shunsen Katsukawa (1790–1823)

Early 19th century

Full-color woodblock print, ink on paper

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Dr. George W. Housner, 2001.21.26

2. Divine Steeds

The Japanese imported more than their artistic styles from China — they also adapted Taoist and Buddhist teachings, which they blended with their native Shinto beliefs.

One Taoist figure incorporated into Japanese artwork was Kinko, a holy hermit. In Japanese art, he is often depicted mounted on the enormous carp that carried him to the Undersea Kingdom. There, sea creatures taught him that all life is sacred.

To the Japanese, the carp (koi) is a symbol of persistence, longevity, and fertility. Land-locked farmers kept carp in ponds to provide food, and then bred them for their beautiful colors. Families fly colorful cloth carp from their homes on Children’s Day.

This work was painted by a follower of Soga Shohaku (1730-1781), who studied traditional Chinese painting with the Kano school. He blended these teachings with those of early Japanese painters, specializing in ink monochrome works.

Buddhist deities also used divine steeds. This peacock carries Kujaku from his home in the heavens to spread kindness and compassion to humans on earth. This painting depicts a peacock similar to a Japanese national treasure prized at a major Buddhist temple in Kyoto — a Chinese silk scroll that also shows a holy figure descending to earth on a peacock.

Kujaku is a wise deity who is compassionate and kind. The artist has depicted the deity seated on the back of a male peacock, whose tail fan is painted in gorgeous detail. Although birds such as the swan are holy within the Buddhist realm, the peacock stands for things of this world, perhaps because of its pride, its service to the deities — and its magnificent appearance.

A toad bears the cheerful Shinto immortal Gama Sennin. The old man, named for the toad familiar who carries him (gama means “toad”), holds the secret of immortality and can make himself young again. Gama Sennin carries a parasol to protect himself from the sun and the rain.

This exquisite miniature sculpture, carved from ivory, is called a netsuke. A Japanese man might use a netsuke to secure a pouch or small box to his kimono, which had no pockets. Many netsuke have witty or symbolic meanings that tie to Japanese tradition and myths.

Hermit Riding a Carp

Attributed to the Shohaku School (1730–1781)

Late 18th century

Scroll painting, ink on paper

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Dr. Jesse L. Greenstein, 2002.4.11

Bodhisattva Kujaku Myo-o

circa 1600

Scroll painting, ink, color and gold on silk

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Patricia Ayers Gallucci, 2002.33.1

Gama Sennin and Toad Netsuke

Carved by Yukisama

Late 19th century

Ivory

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Al and Frieda Kaplan, 1997.16.23

3. Beasts and their Wise Men

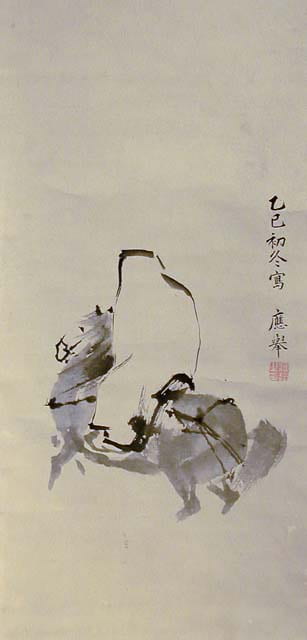

The artist, Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795), has painted an Immortal’s horse in such a way that we sense the animal’s weariness. This celebration of the rigors as well as the beauties of life falls into the Chinese Chan (Zen in Japanese) tradition of paintings, which is full of humor and spontaneity. These paintings depict their subjects with great simplicity — a horse is sketched in only a few strong, dark outlines filled in with pale inkwashes.

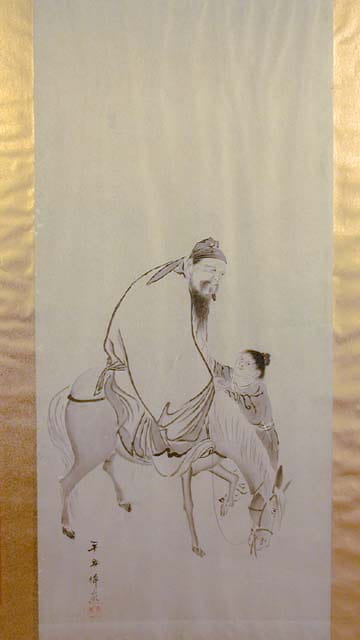

The Chinese Immortal on Horseback is an early example of the work of Maruyama Okyo, an artist who is best known for his realistic depictions of birds and animals. In his early career Okyo took lessons from a Kano school artist in Kyoto and studied the work of old Chinese masters, copying their style of ink painting.

This simple painting focuses on the horse, a powerful animal that materializes out of the fog. Although the brushstrokes seem insubstantial, just a few lines convey the horse’s strong muscles and its mane and tail blown by the wild weather. The rider, only a rough shape on the horse’s back, is cloaked against the cold.

Like the Chinese Immortal on Horseback, this work — showing a sage or a teacher on a journey — was painted by Maruyama Okyo. Unlike Western artists, Japanese painters might paint in different styles from one day to the next.

Artist Nakabayashi Chikuto said that painters should “learn from the great traditions…and be in no hurry to establish an individual style. In due course the inner nature of the painter cannot help but shine through every example of his brushwork.”

The horse is one of twelve animals in the Chinese and Japanese zodiac, which follows a twelve-year cycle. People born in the Year of the Horse are thought to be intelligent, independent, and free-spirited.

Chinese Immortal on Horseback

Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795)

circa 1760s

Ink on paper; originally one panel of a two-panel

screen

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Calvin Frazier, 1986.67.9

Sage on Horseback

Attributed to Maruyama Okyo (1733–1795)

circa 1769-1789

Scroll painting, ink on paper

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Dr. George W. Housner, 2001.21.71

4. Strong as an Ox

The ox is one of twelve animals in the Japanese and Chinese zodiac. It is believed by people in China and Japan that people born in the year of the ox are, like the farmyard animal, quiet and patient.

But not this ox. It charges forward, carrying a scholar on his back. The man clings to the ox’s back with one hand and carries a scroll in the other.

The Zen master Gibon Sengai (1750-1837) painted this work in a simple and spontaneous style. Perhaps he wrote the text that runs from the top right with just a few strokes of the brush — the first ideogram is heavy with ink, and the final stroke is dry and bristly.

Japanese calligraphy and painting use the same ink and often the same brushes. Calligraphers weave words and pictures together to create a vivid impression.

Artist Kawamura Bumpo (1779-1821) presents a naturalistic scene that shows an ox and peasant working together. The artist was known for his sympathetic depictions of every-day life in rural Japan.

Man on Ox

Gibon Sengai (1750–1837)

circa 1800

Scroll painting, ink on paper

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Dr. Jesse L. Greenstein, 2002.4.1

Peasant with Ox

By Kawamura Bumpo (1779–1821)

circa 1810

Scroll painting,ink and color on paper

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Bruce Ross, 1989.56.2

5. Birds of a Feather

A gaggle of white-fronted geese catches a few minutes of rest on their long autumn migration south for the winter. This work by an unknown artist is a beautiful painting of a natural scene, but, like many Japanese artworks, it also evokes human emotions, beliefs, and traditions. The geese — pausing on their journey during fall, when the weather begins to turn cold and plants die back for the winter — suggest the Buddhist idea that everything in life is impermanent, that all plants and animals are born, reproduce, die, and decay.

Chinese monks began painting wild geese in the thirteenth century. These works became popular with students visiting from Japan. A work created at the beginning of the Edo period, such as this panel showing resting geese, might look similar to one created three hundred years before or by a traditionally trained artist working today.

Traditional artists copied from the works of their teachers and from painting manuals. Unlike Western art, which values creativity and innovation over technical ability, Japanese and Chinese artists cherished works that drew on their on their long artistic traditions and technical mastery of their artforms.

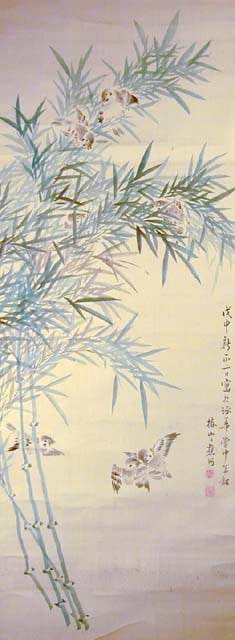

In Japan, the sparrow has traditionally symbolized happiness, and bamboo represents flexibility and resilience. The two symbols are often shown together in painting and other art forms. This light-hearted painting depicts a group of sparrows in a bamboo grove. Some are perched on the bamboo, while others are flying around playfully.

Tsubaki Chinzan (1801-1854) was the foremost pupil of Watanabe Kazan (1793-1841), an artist who studied various Chinese and Western painting styles. He was particularly known for his landscapes and bird-and-flower paintings, which were generally based on Qing dynasty (1644-1911) Chinese prototypes. Chinzan also excelled at Qing dynasty Chinese-style paintings of birds, flowers, and insects, which are often quite colorful and decorative.

In Japan, the crane stands for long life and good luck. These tall and elegant birds are well-suited as subjects for folding screens used in Japanese homes to block drafts and partition rooms.

In Japan today, if you want to wish someone well or a hope for their speedy recovery from an illness, you give them one thousand origami cranes.

Geese

16th century

Two-panel screen, paper, ink, and silk

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Anonymous Donor, 2004.2.1

Sparrows and Bamboo

Tsubaki Chinzan (1801–1854)

1848

Scroll painting, ink and color on silk

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Gerald Kamansky,

1985.56.2

Three Cranes and Bamboo

Early Edo period; Genroku reign (1688-1703)

Two-panel screen, ink, color, and gofun on gold leafing

USC Pacific Asia Museum Collection

Gift of Gail Melhado, 2003.43.1

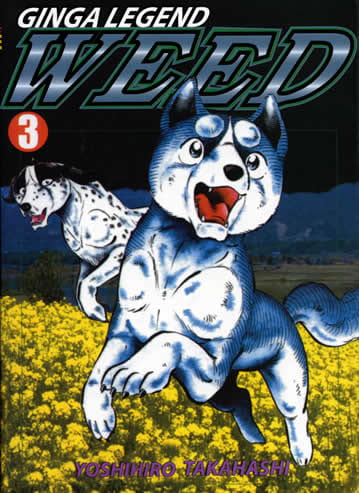

6. Ginga Densetsu Weed

You see them everywhere in Japan. Working women and men on subways read them, kids standing on buses have their noses in them, and students in coffee shops pore over them. Manga, the Japanese word for “comic book,”are everywhere.

The word manga (manga is both singular and plural) has been used since the late 1700s to describe informal drawings and sketches. The artist Hokusai, for example, called his sketchbooks “manga.” Before that time, scrolls that used a sequence of words and images were created for aristocrats and priests, which meant that the number of people who could experience each work was very limited. Printed books meshing dialogue and images were produced in Japan in the late 1800s, and audiences for these often humorous works grew to be enormous.

Manga artists draw animals and people using a very simple style. Eyes are huge, other features are small, and figures are stylized. Although some manga artists are innovative and experimental, most mainstream manga artists follow unwritten rules about the way characters should be drawn.

Ginga Densetsu Weed or Galaxy Legend Weed is a popular manga published today that appeals to young children. The wolf-dog named Weed is the son of the legendary Gin, who founded dog utopia in the Ohu Mountains. Even though Weed is a young puppy, he is called up to avenge the death of his mother and find his long-lost father. Like characters in most modern manga, Weed is a stylized drawing of a puppy. He has traditional Japanese comic features: enormous eyes and exaggerated muscles. His exploits are not typical of most real dogs but instead channel the readers’ desire to feel powerful and accomplish great things.

Ginga Legend Weed (Galaxy Legend Weed) Yoshihiro Takahashi

Japan, July 2000

Published by Nihonbungei-sha.Ltd.

Anonymous Loan